The Penn Museum purchased NEP-80 in November, 1924 after a protracted negotiation process with the Cairo-based dealer Dimitri Andalaft. George Byron Gordon, director of the Penn Museum and the agent who acquired NEP-80, first purchased a manuscript of the Qur’an from Andalaft in April 1920. His next transaction with Andalaft began in October 1923. Gordon returned to Philadelphia with four objects from Andalaft’s shop to evaluate their authenticity and decide on their purchase. A year later following extensive back-and-forth between then two parties, Gordon returned two of the objects and purchased NEP-80 and a Burdah prayer book for a fraction of what Andalaft claimed was the tentatively agreed-upon cost.

To construct the following narrative, we approach our primary sources as unreliable and strategic representations of a negotiation between two parties. Our recapitulation is fraught by a limited archive and the strategic nature of negotiations. The primary sources consist of six letters and a telegraph from Andalaft to Gordon, two invoices (one receited and one not) from Andalaft to Gordon, and a single letter from Gordon outlining the terms of the October 1923 agreement regarding the four objects with a signature of acknowledgement by Andalaft. Thus, our materials overwhelmingly represent Andalaft’s perspective. Further complicating matters, Andalaft’s statements and recapitulations were part of a negotiation.

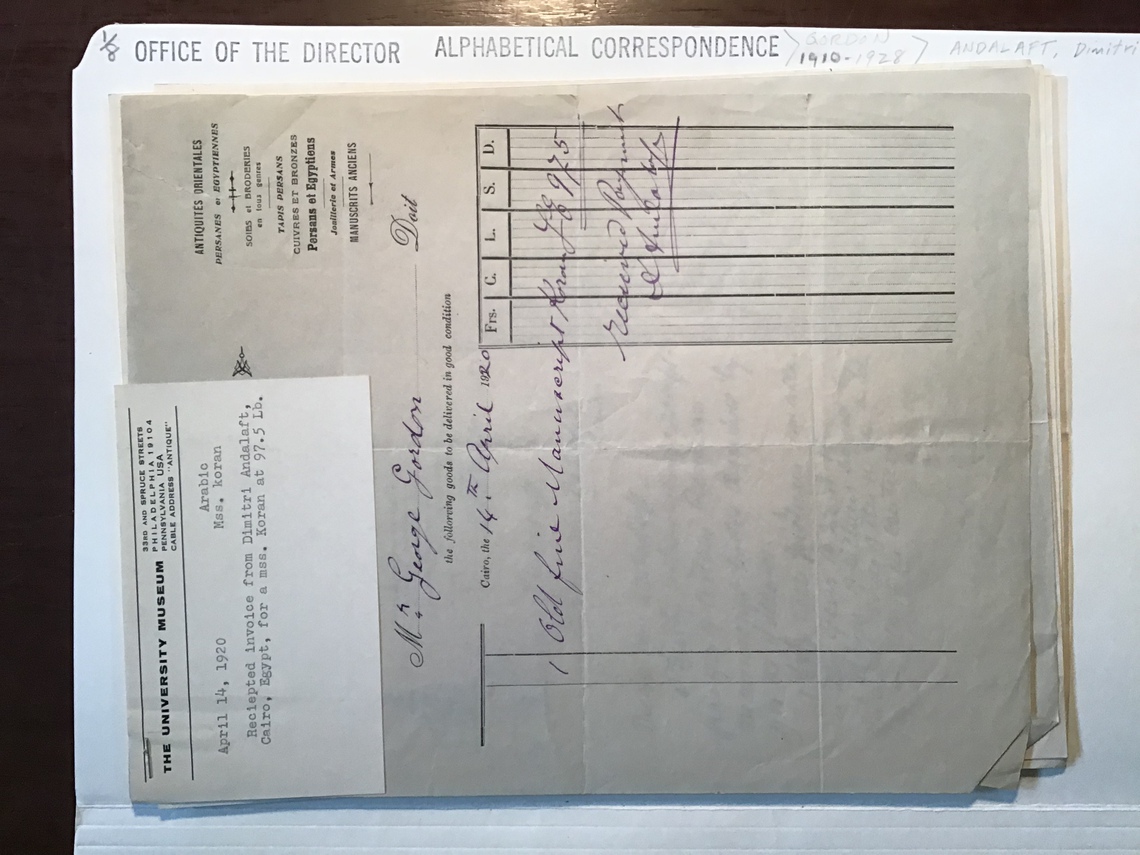

Even with these complicating factors, correspondence between Gordon and Andalaft illustrates how the former leveraged the prestige of academic expertise and his ease of movement to drive down the price of NEP-80. Gordon first purchased “1 old fine manuscript Koran” from Andalaft on April 14, 1920 for a little under 100 Egyptian pounds.

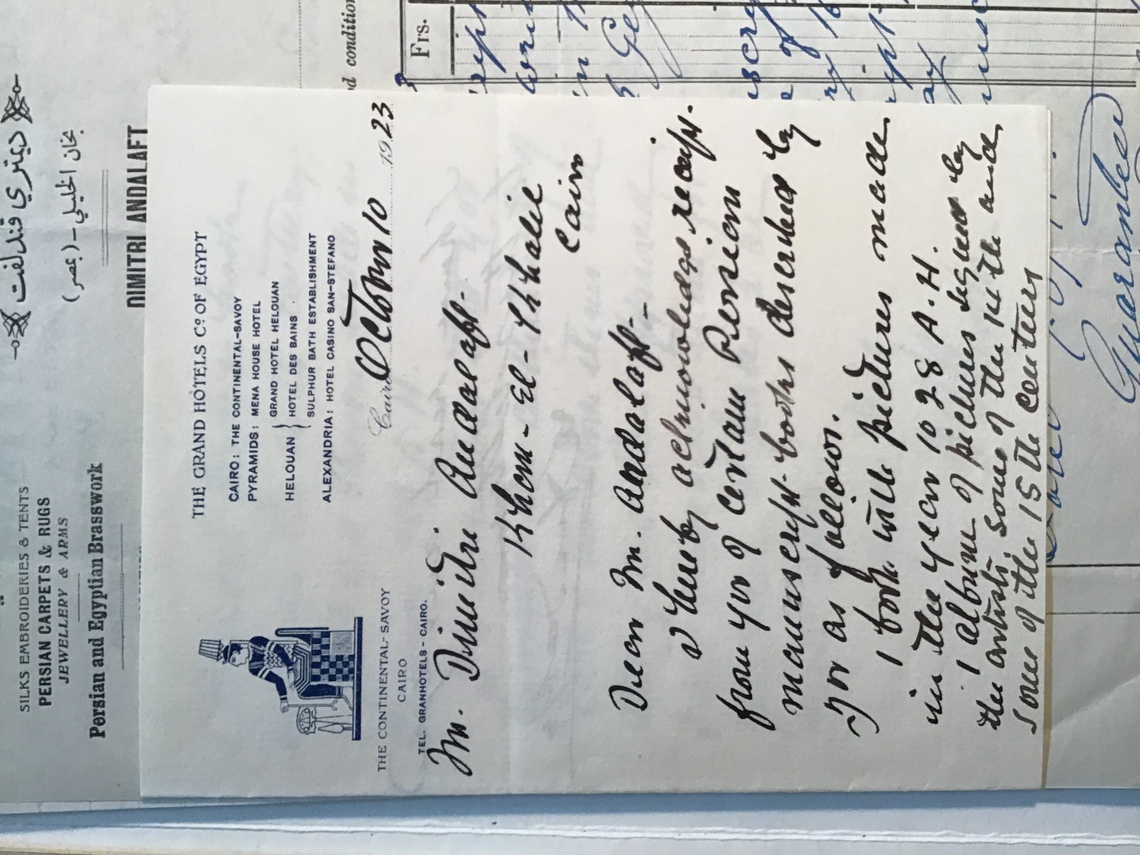

Gordon later returned to Andalaft’s shop in Khan El-Khalili in the late summer and then early fall of 1923. Exactly what took place during their meetings is unclear—all we have are Andalaft’s recollections in his letters to Gordon. Andalaft claims in a May 1924 letter that he initially priced four items at 3650 Egyptian pounds and Gordon countered with 2000 Egyptian pounds and then suggested that he bring them back to the US where he could confirm that they would be worth more than 2000 Egyptian pounds. Gordon’s promissory note writes instead that after confirming the authenticity of the items he will “purchase at prices to be agreed upon.”

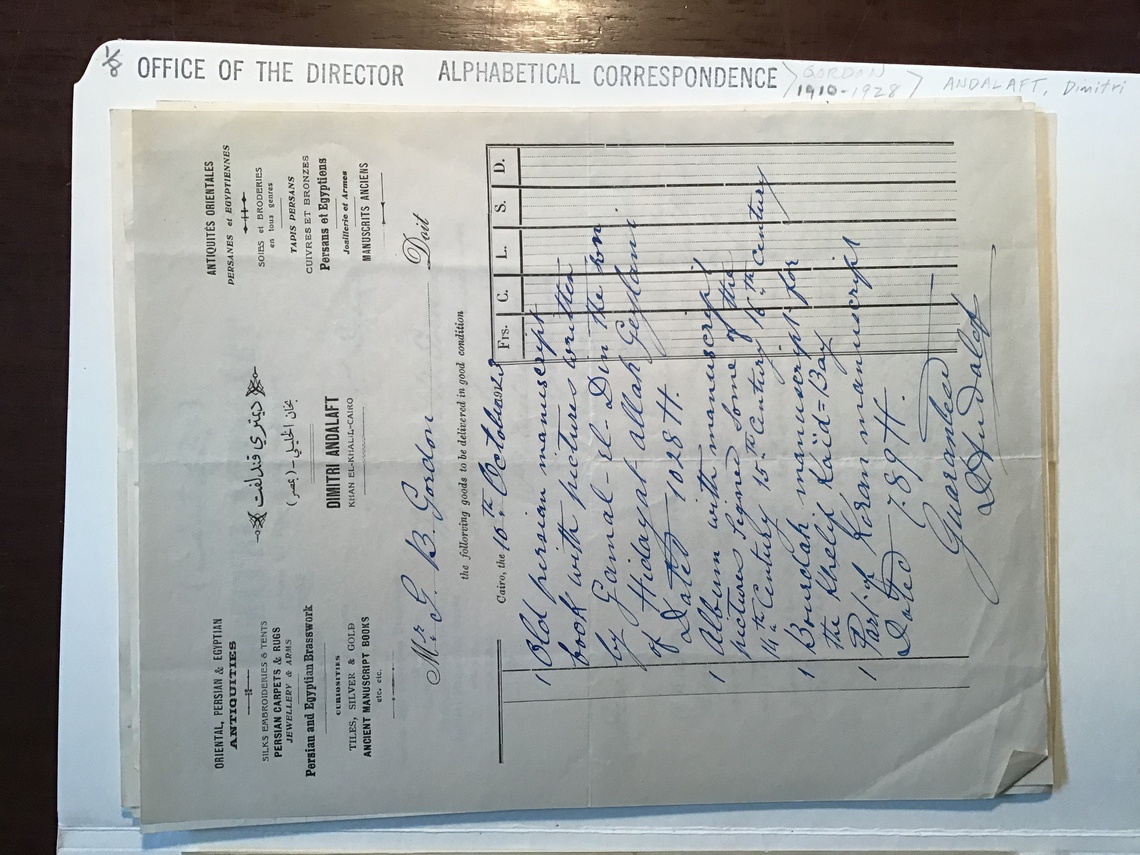

Regardless of the content of this negotiation, Gordon left Andalaft’s shop on October 10, 1923 with one Persian book manuscript dated 1028 AH, one album of signed miniature paintings, one Bourdah manuscript, and a “Persian” Koran manuscript, NEP-80.

From that October 10, 1923 until November 8, 1924, Andalaft sent Gordon one telegram and six letters that variously inquire about the status of payment, reject Gordon’s offers, demand the return of the books on account of insultingly low offers, confirm receipt of the books, and, finally, confirm receipt of a check of payment for NEP-80 and the Burdah prayer manuscript. Andalaft’s typed February 1924 letter communicates that Gordon consulted experts who deemed the book manuscript and album of miniatures to be forgeries.

Even if we read Andalaft’s lamentations as a bargaining strategy, Gordon held onto two books without payment for a 9-month period from October, 1923 until June, 1924. Gordon’s possession of these works deprived Andalaft of the chance of selling them to tourists or buyers, a predicament frequently mentioned by Andalaft.

Moreover, Gordon seems to have leveraged the opinions of a network of experts to drive down the price for the objects. In the case of the Persian book manuscript and the album of pictures, Andalaft refused the price and Gordon returned the items—though, some issues at the post office resulted in Andalaft purportedly paying a 45 pound fine.1 We do not possess records about who Gordon consulted or the specifics of their expert opinions. Gordon’s connection to the authoritative production of knowledge about these objects meant that he could determine unilaterally their authenticity and, consequently, their market value.

Gordon would eventually pay 287 Egyptian pounds for NEP-80 and the Burdah manuscript supposedly produced for Khalil Kaïd Bey. A very generous reading of this price, which is far less than the 2000 pounds Gordon is said to have initially offered for the four works, is that Gordon cunningly sniffed out a duplicitous merchant’s price gouging and consequently acquired the items for a fair price. While there may be some truth to this—perhaps Andalaft was knowingly passing off forgeries as authentic—the delay of payment and transatlantic possession of the items by Gordon afforded him enormous bargaining power in the transaction with Andalaft. Even if he did not have weight of military force behind him, Gordon’s university post allowed him to deem certain items valuable, determine appropriate prices, and withhold payment indefinitely.

It is a credit of the Penn Museum that their archives document the asymmetric negotiation that swelled their holdings. The story contained in these archives is not necessarily flattering for the Penn Museum or Gordon, even if they are not damning in a simple manner. Future research might examine Gordon’s negotiation strategies for other objects or the networks of experts he and other university museum agents consulted in formulating opinions about prices. Additionally, future research might compare and contrast the negotiation strategies and practices of different university museums.

Notes

1: Andalaft claims that the initially 100 pound fine stemmed from Gordon listing the mailed items as being of no value, which the Egyptian authorities believed to be a lie—perhaps a means of skirting the customs fee for the objects. Andalaft claims that the authorities eventually lowered the fine to 45 pounds. Whether Andalaft is telling the truth about the fine, or whether Gordon is responsible for the fine (perhaps it was a case of authorities using their office for material gain) cannot be certain.